by Chelsea Mochizuki

I’m sure you’ve seen them at one point in time, displayed along the aisle shelves of drugstores in cultural and “racial” melting pots like the United States—makeup and hair products marketed to “enhance” and “accentuate” the “natural” features of certain races. However, there is no one physical trait that all members of a racial group share; all “Blacks” do not have x amount of melanin in their skin, all “Asians” do not have almond-shaped eyes with a curvature of y, and all “Japanese” do not have hair with a diameter of z. So how is it we learn to associate, define, and read physical traits and racial categories?

Let’s see this process in action. Try to imagine a “Black” person. Next, imagine a “White” person. Okay, now imagine a “Japanese” person. How did you draw them? What features do they have? How did you know what features to give each “race”? We learn to expect the way people look like based on our encounters in the social world- through interactions in our daily lives and through popular media representations of “races”. Through this cultural learning process, we internalize how to code race and categorize individuals based on what we think they should and should not look like compared to other “races”.

Terry Kawashima illustrated this social phenomenon using the racial “ambiguity” of characters from Japanese shojo manga. Will a manga character with a small mouth, straight tall but small nose, large “saucer” eyes, and blond hair be recognized as “Japanese” or “White”? According to Kawashima, American audiences tended to view this character as “White” because it had blond hair, while Japanese audiences tended to view this same character as “Japanese” because of its small mouth and nose. Americans were surprised that this character is also thought of as “Japanese” because Americans tend to learn that blond hair is a central indicator of “Whiteness”, while Japanese audiences tend to learn that blond hair does not necessarily indicate being “White” in combination with other telling features of “Japanese-ness”. Different cultures and societies have their own set of rules and criteria for defining and categorizing “races”, which accounts for the differences in the way American and Japanese audiences code the character. We are taught what traits define which races, and what races should or shouldn’t have which traits.

I remember when I was a child growing up the United States, and children would mock Chinese people (this term was all-encompassing to mean anyone of East-Asian “descent”), by pulling the outer corners of their eyes towards their ears to form a more almond-looking shape, and yell “ching-chong” to imitate the “Asian” language. While both my parents and I identify as “White” and are viewed by society as “White”, I remember thinking that both my mother and many other of my “white” acquaintances also had smaller, almond-shaped eyes, so I did not understand why “almond eyes” were a trait associated with “Asian-ness”. As I entered high school and became more aware of and interested in Japanese popular culture, I began to notice differences in the way “Asian-ness” or “Japanese-ness” were represented in the media. When I showed pictures of the Japanese pop singer Ayumi Hamasaki to my peers, they said her “orange” hair was weird and here eyes were too “big”; in other words, they came to the conclusion she was trying to be “White”, when she should otherwise be accentuating her “Asian” features because she is racially perceived as “Asian”.

Famous Japanese pop singer Ayumi Hamasaki

In comparing Japanese media representations of Ayumi Hamasaki to images of Lucy Liu, who was embraced by American popular media and described by Kawashima, there are noticeable differences in the appearances of these women. Ayumi Hamasaki’s makeup gives her eyes a large and rounded appearance, while Lucy Liu’s makeup leaves her eyes in an “almond” shape- just as “Asians” are expected to look by American audiences. You may speculate that Ayumi Hamasaki enlarges and thus in-authenticates her eyes using makeup techniques or has undergone plastic surgery, but in arguing so, you are giving in to socialization processes and assuming that “natural” Asian eyes are almond-shaped, and therefore cannot “naturally” be “saucer shaped”.

Lucy Liu, who was generally embraced by American popular media

This blog is not attempting to define or identify any defining physical characteristics of each race; race is in the eye of the beholder- what is authentic, what is natural. Women are often told they should accentuate their natural features—follow the natural curves of your face when contouring, play up your lips if they are naturally plump, and so forth, but this becomes a problem when “naturalness” and “authenticity” are racially coded. If you are “White”, makeup leaving you with deep-set eyes and medium-high cheek bones is viewed “authentic”; if you are “Asian”, any makeup that does not render your eyes in an “almond” shape is “inauthentic”. If there are many physical variations of the same features among members of the same “race”, why does “natural” makeup for each race only portray one set of variation of physical features?

I will be sure to think of Kawashima’s work, the next time I hear someone say “It’s such a waste that he/she is hiding his/her “natural White/Asian/Black/Brown” features”. There are no physical traits “natural” or essential to any one race, so why should one race have just one “natural” or “authentic” form of makeup and beauty alteration? We must re-examine the innate racialization of “natural” beauty.

Reference

Kawashima, Terry. 2002. “Seeing Faces, Making Races: Challenging Visual Tropes of Racial Difference in Japan.” Meridians 3(1):161-190.

It is easy to recognize Japanese Manga characters from their exaggerated round eyes, small nose, spindly legs and colorful hair. These features that are generally common for most Japanese readers confuse Western readers sometimes because in their eyes Manga characters look like Caucasians but Japanese. In Kawashima’s article, many Westerners consider stylized Manga figure as an expression of “trying to be white” and the idea of “becoming white” is a product of cultural imperialism since the white people were historically dominant in the world. They even express their sympathy to “Asian people” who try to become white by stating that their should stay who they are but not constrained to racial hierarchy thinking. In fact, the thought of regarding Manga figures as white or trying to be white is a symptom of visual production of race and racial privilege thinking.

It is easy to recognize Japanese Manga characters from their exaggerated round eyes, small nose, spindly legs and colorful hair. These features that are generally common for most Japanese readers confuse Western readers sometimes because in their eyes Manga characters look like Caucasians but Japanese. In Kawashima’s article, many Westerners consider stylized Manga figure as an expression of “trying to be white” and the idea of “becoming white” is a product of cultural imperialism since the white people were historically dominant in the world. They even express their sympathy to “Asian people” who try to become white by stating that their should stay who they are but not constrained to racial hierarchy thinking. In fact, the thought of regarding Manga figures as white or trying to be white is a symptom of visual production of race and racial privilege thinking. I have been a big fan of Manga and Anime for as long as I can remember. I always admired how the Japanese style of drawing cartoon characters was different from that of popular western comics and animations. The characters in Manga and Anime have always stood out because they are unique. That is, many of them have exaggerated and flamboyant features and this always stood out for me and many other fans alike. Never did it ever occur to me that the way the Japanese creators illustrate their artistic work had significance on how race and ethnicity is viewed or construed in Japan.

I have been a big fan of Manga and Anime for as long as I can remember. I always admired how the Japanese style of drawing cartoon characters was different from that of popular western comics and animations. The characters in Manga and Anime have always stood out because they are unique. That is, many of them have exaggerated and flamboyant features and this always stood out for me and many other fans alike. Never did it ever occur to me that the way the Japanese creators illustrate their artistic work had significance on how race and ethnicity is viewed or construed in Japan. apparently) who is the leader of the Askari (Swahili word to mean soldier) which is an African revolutionary organization. Bugnug is first introduced to Crying Freeman manga readers when she launches a surprise attack on Yō Hinomura who is the main character. She is illustrated to look ‘exotic’. She is beautiful with long curly hair but is muscular and masculine in her behavior. It is impossible to compare her to the other Japanese females in the same manga as they seem more fragile and feminine.

apparently) who is the leader of the Askari (Swahili word to mean soldier) which is an African revolutionary organization. Bugnug is first introduced to Crying Freeman manga readers when she launches a surprise attack on Yō Hinomura who is the main character. She is illustrated to look ‘exotic’. She is beautiful with long curly hair but is muscular and masculine in her behavior. It is impossible to compare her to the other Japanese females in the same manga as they seem more fragile and feminine. During the battle with Yō Hinomura (Crying Freeman), Bugnug is completely naked and only carries a blade. When she is finally defeated by Yō Hinomura, the two become allies and she later on gets his assistance to defeat a coup d’état in her organization. It seems as though the creators of this manga and anime went all out to display Bugnug’s supposed ‘Africanness’ by naming the character Bugnug which they go on to translate as Ant-Eater, having her fight naked, which I believe represents a kind of primitiveness and then including a coup d’état in her storyline which occurs within her revolutionary organization. So this leaves me to question why some characters of African ancestry are represented in this manner in manga and anime. Do all the people of African ancestry have these characteristics and why have these stereotypes been continuously perpetuated?

During the battle with Yō Hinomura (Crying Freeman), Bugnug is completely naked and only carries a blade. When she is finally defeated by Yō Hinomura, the two become allies and she later on gets his assistance to defeat a coup d’état in her organization. It seems as though the creators of this manga and anime went all out to display Bugnug’s supposed ‘Africanness’ by naming the character Bugnug which they go on to translate as Ant-Eater, having her fight naked, which I believe represents a kind of primitiveness and then including a coup d’état in her storyline which occurs within her revolutionary organization. So this leaves me to question why some characters of African ancestry are represented in this manner in manga and anime. Do all the people of African ancestry have these characteristics and why have these stereotypes been continuously perpetuated? This exposure has been both positive and negative in that it has opened up Japan to other cultures and has made the Japanese people more aware of the differences between their cultures, traditions and those of people from other parts of the world but has also promoted the adoption of negative stereotypes thus most of what the Japanese know are imagined racial distinctions that have been created and promoted by the western media.

This exposure has been both positive and negative in that it has opened up Japan to other cultures and has made the Japanese people more aware of the differences between their cultures, traditions and those of people from other parts of the world but has also promoted the adoption of negative stereotypes thus most of what the Japanese know are imagined racial distinctions that have been created and promoted by the western media.

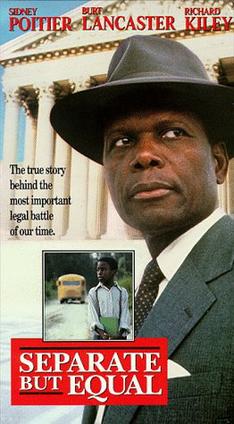

For more information about the racial segregation and Clark Doll Experiment, I would like to recommend the movie, Separate But Equal.

For more information about the racial segregation and Clark Doll Experiment, I would like to recommend the movie, Separate But Equal. Manga are a topic that has been well-researched in Japanese Studies. However, when it comes to racial identity, we can see strong wonders about the racial identity found in the manga characters. On the one hand, if you search on the internet the question in English “Do Manga look like white people”, you have 14,000,000 results. On the other hand, if we do the same search in Japanese “漫画キャラクターは白人っぽい“, you only get 736,000 results and it is mainly a translation on the question asked by foreigners.

Manga are a topic that has been well-researched in Japanese Studies. However, when it comes to racial identity, we can see strong wonders about the racial identity found in the manga characters. On the one hand, if you search on the internet the question in English “Do Manga look like white people”, you have 14,000,000 results. On the other hand, if we do the same search in Japanese “漫画キャラクターは白人っぽい“, you only get 736,000 results and it is mainly a translation on the question asked by foreigners. Terry Kawashima (2002), in her essay “Seeing Faces, Making Races: Challenging Visual Tropes of Racial Difference,” argues that the manga characters are mainly based on whiteness’ particularities and they influence the young women when it comes to the concept of beauty. According to her, the manga readers had been “culturally conditioned to read visual images in specific racialized ways that privilege certain cues at the expense of others and lead to an over determined conclusion” and highlight the issues on how “race” is a social constructed category.

Terry Kawashima (2002), in her essay “Seeing Faces, Making Races: Challenging Visual Tropes of Racial Difference,” argues that the manga characters are mainly based on whiteness’ particularities and they influence the young women when it comes to the concept of beauty. According to her, the manga readers had been “culturally conditioned to read visual images in specific racialized ways that privilege certain cues at the expense of others and lead to an over determined conclusion” and highlight the issues on how “race” is a social constructed category. So why do we see specific racial features in these “odorless” characters? It is mainly because of our personal representation of racial differences. These differences are called “markedness” by Matt Thorn (2004), we used our own culture and features of our own personal experiences to identify the character’s race. For example, look at a manga character with blond hair and blue eyes who is eating a bowl of rice with chopsticks. Where a French person will see a French personage because of its physical features and because he is himself French, the Japanese will see a Japanese person because this he/she is eating a bowl of rice with chopsticks.

So why do we see specific racial features in these “odorless” characters? It is mainly because of our personal representation of racial differences. These differences are called “markedness” by Matt Thorn (2004), we used our own culture and features of our own personal experiences to identify the character’s race. For example, look at a manga character with blond hair and blue eyes who is eating a bowl of rice with chopsticks. Where a French person will see a French personage because of its physical features and because he is himself French, the Japanese will see a Japanese person because this he/she is eating a bowl of rice with chopsticks.