By Ye Tiantian

I chose this topic because I myself am a part of the skin whitening market, as I have been consuming skin lightening products since I don’t even remember when. But for all that time, I never asked myself the question of why do I want to whiten my skin? Well, go to any drug store or large mall and ask those purchasing the skin whitening products this question, I am pretty sure that most, if not all, of them will tell you, because they want to be beautiful. But why is white beautiful? That’s the point.

Evelyn Nakano Glenn’s research introduced the skin whitening markets in different regions and among different consuming groups. Glenn used the word “colorism” to explain the growing and even illegal skin whitening markets in African nations which is related to colonialism and the so-called “white privilege”. I don’t know much about the skin whitening market of Africa, African America, India, Southeast Asia or Latin America. Actually, I didn’t even know that there exist such huge skin whitening markets outside Asia until I had read Glenn’s research, since I had always assumed that it is the traditional Asian aesthetic that lead to the practice of using those products. But I do know the whitening market of East Asia or more specifically China.

It is true that I cannot represent all of the consumers in the skin whitening market, but I am pretty sure that I and most of the people I know buying those products are not trying to make ourselves look like white people. We don’t want to be white, we want to be what in Chinese we called “白里透红”, white with rosy touches, like the skin of a newborn baby—an Asian baby, not necessarily a white baby.

As we have discussed before, race is a socially constructed category. It is not like only white people have the biological gene to have white skin. Compare the skin color of a newborn Asian baby with a white person, they are not that different. I cannot tell you for sure that it has nothing to do with white privilege that people like me buy skin whitening products. But at least, I believe this is not the whole story behind the growing skin whitening market in at least China.

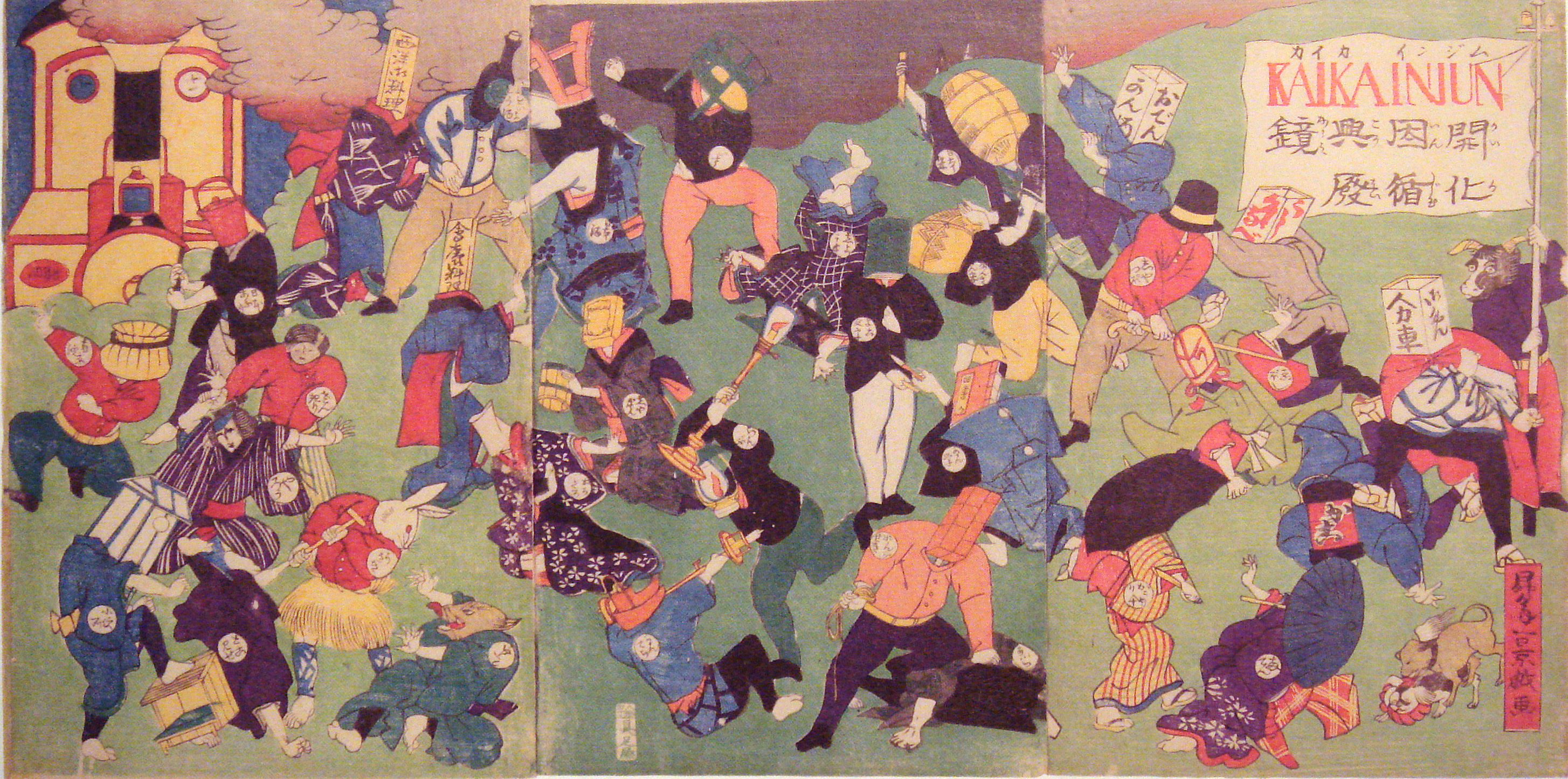

If it is all about the white privilege, how can we explain that the practice of skin whitening in China could date back to Qin Dynasty (221-206BC)? Women in China at that time already learnt to make their face white using lead powders, changing their diets and consuming certain kinds of herbals. If you know a little bit about Chinese history, you will know that China used to be one of the most powerful nations of the world; it was even more powerful than Western European nations. If it was only about white supremacy, as it was believed for the African market, it won’t make any sense because there was no such thing as white supremacy in ancient China.

There is one explanation which I highly doubt, but might be true, that the first ruling class of China as a nation, though not united, is white Indo-Europeans. Thus, white skin is linked with the ruling class. But this cannot be entirely proved and for most time of the Chinese history, the rulers were not white people.

My guess is that Chinese want to be white because whiter skin (not pure white skin like white people) is linked with higher social classes inside the Chinese society. From the Qin dynasty, there is this a social ranking in which scholars and officers were always on the top of the social class. What’s the characteristic of scholars or officers? They work indoors, not outdoors. Thus, they are not exposed to sunshine as other farmers, workers, merchants are, and as a result they must have skin more like that of newborn babies. We even have a word for it in Chinese, “白面书生”. Thus, in the traditional stereotype of Chinese society, whiter skin is linked with higher social class.

This is even true for contemporary Chinese society. We may be educated to treat all kinds of jobs equally and be taught that there is no such thing as better jobs and worse jobs. But the unconscious bias of our mind still to some extent controls our behaviors. And from my observation, there must be such bias and sometimes even conscious ones.

Sometimes, this kind of discrimination is even institutionalized. In the Chinese hukou system, people possessing a rural hukou receive a lower standard of social welfare compared with people with an urban hukou. Those people with rural hukou are normally those working as agriculture farmers or construction workers and other labor intensive jobs. People working in the offices normally have higher social status compared with people working outdoors in construction sites or agricultural fields. A typical image of a successful person working a decent job would be like this, while “migrant workers” or farmers are usually associated with this kind of image and are usually considered as poor, not well-educated and with bad manners.

So my argument is that the preference of white skin may be linked with power and privilege, but it doesn’t need to be privilege of other races and ethnic groups. While white privilege might be an explanation for the skin whitening market in some parts of the world, some times it could because of the privilege of social classes inside the same race and ethnic group. Being whiter doesn’t need to be imitating white people.

by Rena Shoji

by Rena Shoji

It is this feeling of disconnect that had made me conscious of my ambiguous racial identity. On one hand I am partially white, does that put me on the side of the oppressor? Did I feel upset because of underlying guilt? But what about the times where I was discriminated against, what about all the times where people told me to go back to China? Was I upset because I was afraid of being a victim of violent discrimination? While it isn’t true, I couldn’t help but feel that there was really no place for me in the conversation about race, I straddled an awkward border of whiteness that made it seem that I didn’t have the right to talk about race as a minority.

It is this feeling of disconnect that had made me conscious of my ambiguous racial identity. On one hand I am partially white, does that put me on the side of the oppressor? Did I feel upset because of underlying guilt? But what about the times where I was discriminated against, what about all the times where people told me to go back to China? Was I upset because I was afraid of being a victim of violent discrimination? While it isn’t true, I couldn’t help but feel that there was really no place for me in the conversation about race, I straddled an awkward border of whiteness that made it seem that I didn’t have the right to talk about race as a minority. by Olivia Katherine Parker

by Olivia Katherine Parker