English: Photo of Mini Facelift Cosmetic Surgery Procedure being Performed by Facial Plastic Surgeon. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

by Kiho Kozaki

Plastic surgery is a widespread phenomenon today, and is more popular and accepted than ever. Aman Garg once said that plastic surgery is a medical specialty concerned with the correction or restoration of form and function. Now some studies and surgeons insist that plastic surgery is the “correction” of facial features. The American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) conducted a survey which is the 17-year national data for procedures performed from 1997-2013, and during that period, there was a 279% increase in total number of plastic surgery both surgical and nonsurgical procedures. Though the statistic covers only procedures done in the United States, I assume that same result would be seen in elsewhere in the world.

The survey also shows that the plastic surgery’s popularity among racial and ethnic minorities, who had approximately 22% of all cosmetic procedures: African-Americans 7%, Asians 5%, Hispanics 8%, and other non-Caucasians 1%. The percentages vary depending on the studies, however, as a common observation, racial and ethnic minorities seem to seek out plastic surgery more than Caucasians.

Nadra Kareem Nittle, a race relations expert, said that is because minority groups still feel pressure to live up to Eurocentric beauty norms. They alter traits such as prominent noses or hooded eyelids. Moreover, weaves, wigs and skin whitening creams continue to enjoy mass appeal in communities of color. Then, this phenomenon of plastic procedures raises a question: do they undergo these procedures in order to look like Caucasians? Or just to gain self-esteem and to look good?

Since the standard of beauty seem to be a Westernized ideal, some people are dissatisfied with their ethnic features and believe they are ugly. Angie Rankman wrote that the appearance of mostly unattainable model normalizes certain body images, and then people perceived problems with their own features. The result is that many people are left with deep seated psychological insecurities about themselves and their body image, often resulting in unreasonable expectations in regard to cosmetic surgery.

As Alexander Edmonds, a lecturer of Anthropology at Macquarie University in Sydney, notes, mass media uses this ‘market value of appearance’. I argue that is not necessary to conclude that they want to look like Caucasians. Of course there is a big influence by mass media remaining people dissatisfied with their features and the desire for Caucasians may exist but that does always not mean they want to cross racial and ethnic lines. Some people may wish to, but I assume that majority of people still want to remain as who they are.

Dr. Samuel Lam, a plastic surgeon cited in Bagala’s article, called it ‘ethnic softening’. It means the softening of facial features that patients deemed overly ethnic but still preserving their ethnicities. Most of the patients are becoming more willing to work with their ethnic features rather than work against them.

Edmonds says there is a slippage between the national cultural notion of a ‘preference’ and a racial-biological notion of a ‘type.’ So, according to Edmonds, operations like breast surgeries can be linked to national but not racial identities.

Plastic procedures are much complicated that we cannot simply conclude why it gets more popular than ever among racial/ethnic minorities. Now, we are in the era of expansion of beauty culture. Though patients who underwent plastic procedures may insist that was their personal choice, and that they wanted to look better to boost their self-esteem, it is not simple as they insist. We should note that their assumptions and beliefs may be constructed from deep-rooted national cultural norms, racial-biological norms and certain expectations of appearance. Right now we are in the middle of seeking a new way of accepting and dealing with the widespread beauty norms.

References

American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. (2013). 2013 ASAPS Statistics: Complete charts [Including National Totals, Percent of Change, Gender Distribution, Age Distribution, National Average Fees, Economic, Regional and Ethnic Information] http://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/Stats2013_4.pdf

Bagala, J. (2010). Saving Face: More Asian Americans opting for plastic surgery. Hyphen Asian America Unabridged, 22. http://www.hyphenmagazine.com/magazine/issue-22-throwback/saving-face-m ore-asian-americans-opting-plastic-surgery

Edmonds, A. (2007). The poor have the right to be beautiful: cosmetic surgery in neoliberal Brazil. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13:363-381.

Garg, A. (n. d.). Plastic Surgery. Cite lighter. http://www.citelighter.com/science/medicine/knowledgecards/plastic-surgery.

Nittle, K, N. (n. d.). Race, Plastic Surgery and Cosmetic Procedures. About News. http://racerelations.about.com/od/diversitymatters/tp/Race-Plastic-Surgery-An d-Cosmetic-Procedures.htm

Rankman, A. (2005). Obsessed With Beauty: The Rush To Cosmetic Surgery. Aphrodite Women’s health. http://www.aphroditewomenshealth.com/news/cosmetic_surgery.shtml

by Umene Shikata

by Umene Shikata

by John Wang

by John Wang

The custom of face-whitening in Japan goes back to

The custom of face-whitening in Japan goes back to

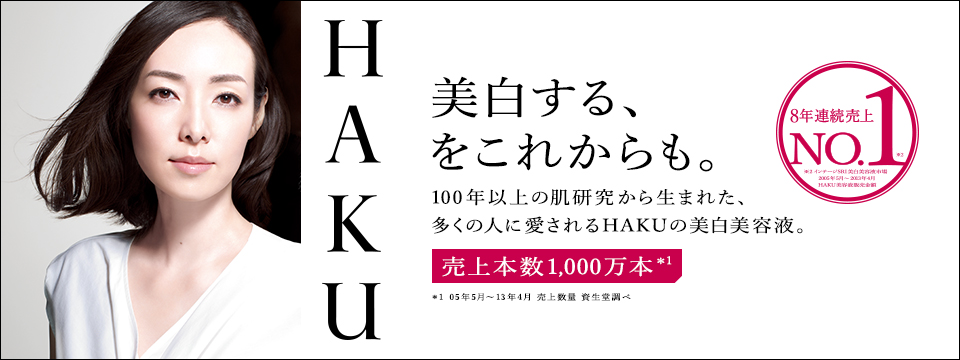

In her research on Japanese whiteness, Mikiko Ashikari (2005) tries to explain where the idea of a specific white skin among the “Japanese race” comes from. According to Ashikari, it seems less likely to be from Caucasians’ influence, since Japanese women considered Caucasian skin as “rough, aged quickly and had too many spots” (Ashikari 2005:82). The idea of white skin in the Japanese society is even more specific than any other features that could define the idea of being “Japanese”. Although Japanese change their hair color with dying products, their eye color with contact lenses, and their physical features with plastic surgery, they would never change their skin color because “the notion of Japanese skin works as one medium to express and represent Japaneseness” (Ashikari 2005:76). As Ashikari notes, by defining a specific skin color to their race, Japanese people are even able to reject the Okinawan people as a “second-class citizens” (Gibney quoted by Ashikari, 2005, p. 80).

In her research on Japanese whiteness, Mikiko Ashikari (2005) tries to explain where the idea of a specific white skin among the “Japanese race” comes from. According to Ashikari, it seems less likely to be from Caucasians’ influence, since Japanese women considered Caucasian skin as “rough, aged quickly and had too many spots” (Ashikari 2005:82). The idea of white skin in the Japanese society is even more specific than any other features that could define the idea of being “Japanese”. Although Japanese change their hair color with dying products, their eye color with contact lenses, and their physical features with plastic surgery, they would never change their skin color because “the notion of Japanese skin works as one medium to express and represent Japaneseness” (Ashikari 2005:76). As Ashikari notes, by defining a specific skin color to their race, Japanese people are even able to reject the Okinawan people as a “second-class citizens” (Gibney quoted by Ashikari, 2005, p. 80). Actually, Japanese whiteness has its roots even before the Black Ships arriving in Japan during the 16th century. It is said that during Nara Period (710–94) and Heian Period (794–1185), Japanese women were already using diverse products to light their skin tone (Kyo 2012). The ideal of white skin is also found in a lot of literature of this period such as the Diary of Lady Murasaki and Tale of Genji (Kyo 2012). Back in the Heian Period, women would blacken their teeth and shave their eyebrows. Nowadays nobody would shave their eyebrows as a sign of beauty but the idea of white skin as the ideal of beauty among Japanese women is still a recurrent topic in Japanese society.

Actually, Japanese whiteness has its roots even before the Black Ships arriving in Japan during the 16th century. It is said that during Nara Period (710–94) and Heian Period (794–1185), Japanese women were already using diverse products to light their skin tone (Kyo 2012). The ideal of white skin is also found in a lot of literature of this period such as the Diary of Lady Murasaki and Tale of Genji (Kyo 2012). Back in the Heian Period, women would blacken their teeth and shave their eyebrows. Nowadays nobody would shave their eyebrows as a sign of beauty but the idea of white skin as the ideal of beauty among Japanese women is still a recurrent topic in Japanese society.

by Lin Tzu-Chun

by Lin Tzu-Chun In China, for example, you have to go find some exclusive shops to buy a KOSE products, but here in Japan they are put at the entrance of many drug stores. This different marketing strategy reminds the Chinese phrase “Bai, fu, mei” or “White, Rich, Beauty”, is that white means you are rich because you are able to consume expensive lightening products. Does that mean that the products might be more effective? If we compare the income difference, it may be true that you really need money to buy expensive cosmetics but there is no guarantee they will be effective. For whiteness, I refer to a common saying in China, “one white covers hundred (three) ugly”, which means that if you are white and make it the focus point of people’s sight, people won’t care much about your other problems.

In China, for example, you have to go find some exclusive shops to buy a KOSE products, but here in Japan they are put at the entrance of many drug stores. This different marketing strategy reminds the Chinese phrase “Bai, fu, mei” or “White, Rich, Beauty”, is that white means you are rich because you are able to consume expensive lightening products. Does that mean that the products might be more effective? If we compare the income difference, it may be true that you really need money to buy expensive cosmetics but there is no guarantee they will be effective. For whiteness, I refer to a common saying in China, “one white covers hundred (three) ugly”, which means that if you are white and make it the focus point of people’s sight, people won’t care much about your other problems.