Anonymous student post

This blog will focus on beauty ideals pertaining to skin color and facial symmetry.

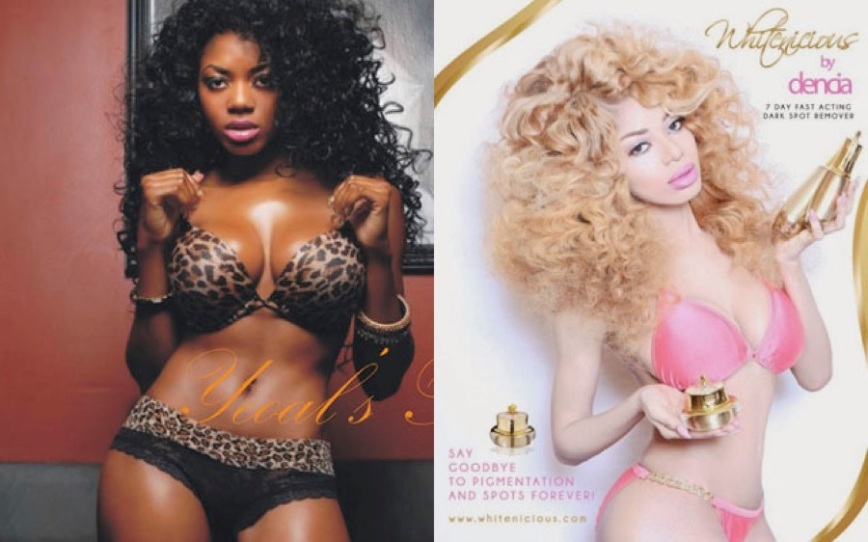

From Asia to Africa, having a light skin tone makes one more desirable. Colonial invasions have only helped to instil the idea ‘the whiter the better’. Even in Africa skin bleaching is quite popular. Especially in Nigeria where 77% of women use skin bleaching aides (Alonge 2014). While many Caucasians may tan, other races may tend to avoid tanning. According to the media, tanned skin on a Caucasian individual represents fitness and vacationing, yet ads showcasing the tanning of other races is rare or non existent.

Perhaps the desire for lighter skin is due to the “colonial mentality” which preaches that “white is right”. Yet in countries such as Japan and Asia the ideal beauty has been pale and to an extent is still considered the ideal. One only needs to search for images of celebrities to know the standard. For many centuries in Asia the color of one’s complexion has been an indicator of class status with pale being at the top (Wagatsuma 1967).

India also has a status system based on the complexion of one’s skin that has been exaggerated since the invasion of colonialism. The main difference between the availability of opportunities between East Asia, India, and Africa is that in Japan and China tanned skin does not affect job opportunities, but dark skinned foreigners stick out and aren’t treated as nicely as their lighter skinned counterparts (Arudou 2014), but in Korea where a profile picture must be attached to a resume (The Grand Narrative 2010), the discrimination is worse; in India dark skinned people use skin bleaching aides in order to secure a ‘good job’ and/or get a successful arranged marriage partner (Glenn 2008); and in Africa women bleach their skin due to self esteem issues and to get married as the ‘colonial mentality’ still exists along with the racial profiling of black skinned people.

Even in the US and Europe there are issues with the degree of one’s skin color yet bleaching is less common. Being lighter than average in complexion in one’s race gives one special privileges such as receiving discounts, extras, and also better behavior such as in not being profiled (Fihlani 2013). Lighter skinned black people receive extra attention yet being too light or albino excludes one from their race yet they are also excluded from the white race group (Parks 2007). Also bias in treating others differently due to skin tone is a form of internalized racism (Hall 1992).

According to research, facial symmetry is preferred over asymmetrical faces. In Rhodes et al.’s study on facial symmetry, males preferred the perfect symmetrical face more than females, but the preferences of all other degrees of facial symmetry was similar between the genders. In experiment 1, three individuals original portraits were shown along with computer-altered images in the order of low, normal, high, and perfect symmetry (Rhodes et al. 1998). The argument for the reason being that facial symmetry is attractive is due to health in childhood, but such evolutionary claims have been debunked as a myth (Poppy 2014).

In westernized nations a low WHR (waist to hip ratio) is preferred over a high WHR, yet the Matsigenka people, who are isolated from westernization, prefer a high WHR. According to the Matsigenka the low WHR looks unhealthy (Yu et al. 1998).

Also infants responded more to images of symmetrical faces than asymmetrical faces by staring at symmetrical faces for a greater duration of time. Not many studies in facial symmetry have been conducted multiculturally yet current issues in South Korea such as plastic surgery being quite popular may suggest that facial and/or body symmetry is quite important (Chang & Thompson 2014).

Perception bias may also influence the concept of facial symmetry as participants in Little and Jones’s experiment didn’t express a preference for symmetrical faces that were inverted, rather such images were perceived as objects than faces (Little et al. 2003). Overall westernized cultures, (meaning not having been influenced by western media) may prefer symmetrical faces and bodies with a low WHR.

Cross culturally in determining beauty a symmetrical face and clear skin are main ideals that remain (Gaad 2010) while ideals such as having fair skin are of Western (Wade 2014) and East Asian origin (Xiea et al. 2013). If one pays attention to the media, the majority of actresses, models, celebrities and those who appear in the media usually have clear, bright skin, and facial symmetry. Also hierarchy due to skin tone may be a cultural issue, but it is most likely not strictly just a cultural issue alone, but also internalized and externalized racism (Hunter 2007).

References

Alonge, Sede. “Not all African women believe ‘black is beautiful’. And that’s OK.” The Telegraph 18 July 2014. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/10973359/Not-all-African-women-believe-black-is-beautiful.-And-thats-OK.html>.

Arudou, Debito. “Complexes continue to color Japan’s ambivalent ties to the outside world.” The Japan Times (2014). <http://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2014/07/02/issues/complexes-continue-color-japans-ambivalent-ties-outside-world/#.VJl6oAABA>.

Chang, Juju, and Victoria Thompson. ” Home> Lifestyle South Korea’s Growing Obsession with Cosmetic Surgery .” ABC NEWS, 20 June 2014. <http://abcnews.go.com/Lifestyle/south-koreas-growing-obsession-cosmetic-surgery/story?id=24123409>.

Feng, Charles. “Looking Good: The Psychology and Biology of Beauty.” Journal of Young Investigators 6.6 (2002). <http://legacy.jyi.org/volumes/volume6/issue6/features/feng.html>

Fihlani, Pumza, and Thomas Fessy. “Africa: Where black is not really beautiful.” BBC NEWS AFRICA. BBC, 1 Feb. 2013. <http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-20444798>.

Glenn, Evelyn N. “Yearning for Lightness Transnational Circuits in the Marketing and Consumption of Skin Lighteners.” Gender & Society 22.3 (2008): 281-302.

Hall, Ronald E. “Bias Among African-Americans Regarding Skin Color: Implications for Social Work Practice.” Journal of Black Psychology 2.4 (1992): 479-86. <http://rsw.sagepub.com.libproxy.library.wmich.edu/content/2/4/479.full.pdf+html>.

Hunter, M. “The Persistent Problem of Colorism: Skin Tone, Status, and Inequality. Sociology Compass” (2007), 1: 237–254. <http://www.mills.edu/academics/faculty/soc/mhunter/The%20Persistent%20Problem%20of%20Colorism.pdf>

Little, A. C. & Jones, B. C. (2003). Evidence against perceptual bias views for symmetry preferences in human faces. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 270: 1759-1763. <http://faceresearch.org/students/symmetry>

Parks, Casey. “Black Woman, White Skin.” Marieclaire.com. N.p., 13 July 2007. Web. 20 Dec. 2014. <http://www.marieclaire.com/politics/news/a557/black-white-skin/>.

Perrett, David et al. Symmetry and human facial attractiveness. Evolution & Human Behavior. 1999 (20): 295-307. <http://facelab.org/bcjones/Teaching/files/Perrett_1999.pdf>

Poppy, Brenda. “Facial Symmetry is Attractive, But Not Because It Indicates Health.” Discover 12 Aug. 2014. <http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/d-brief/2014/08/12/facial-symmetry-attractive-not-because-indicates-health/#.VJlWpAAAM>.

Rhodes, Gillian, Fiona Proffitt, Jonathon M. Grady, and Alex Sumich. “Facial symmetry and the perception of beauty.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 5.4 (1998): 659-69. <http://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/BF03208842>

Saad, Gad. “Beauty: Culture-Specific or Universally Defined? The universality of some beauty markers.” Psychology Today (2010). <http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/homo-consumericus/201004/beauty-culture-specific-or-universally-defined>.

The Grand Narrative. “Korean Sociological Image #40: As Pretty as a Picture?” The Grand Narrative: Korean Feminism, Sexuality, and Popular Culture, 16 June. 2010. <http://thegrandnarrative.com/2010/06/16/korean-resumes-photographs/>

Wade, L. (2014, May 16). When White is the Standard of Beauty. The Society Pages. <http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2014/05/16/white-as-beautiful-black-as-white/>

Wagatsuma, Hiroshi. “The Social Perception of Skin Color in Japan.” Daedalus 96.2 (1967): 443-97. <http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/20027045?sid=21104921217471&uid=2129&uid=4&uid=2&uid=70&uid=3738328>.

Xiea, Qinwei (Vivi), and Meng Zhang. “White or tan? A cross-cultural analysis of skin beauty advertisements between China and the United States.” Asian Journal of Communication 23.5 (2013).

Yu, D W., and G H. Shepard. “Is Beauty In the Eye of the Beholder?” Nature (1998): 396, 321-322+. <http://www.academia.edu/296731/Is_Beauty_In_the_Eye_of_the_Beholder>.

by Kiho Kozaki

by Kiho Kozaki

by Rena Shoji

by Rena Shoji by Olivia Katherine Parker

by Olivia Katherine Parker

by Chloe Lyu

by Chloe Lyu Nevertheless, the reality tells a different story, from the statistics it is obvious that white Brazilians have more opportunities accessing education, work, and a higher standard of living. Despite the race-mixing, the white Brazilian population still occupies the top of Brazilian society, while black and brown people are largely struggling in poverty; Racial democracy is a myth and never actually existed. The colour classification, which has been promoted as a wonderful racial democratic system, sugars up the racial differences and inequality by obscuring the concept of race. In fact, colour and race are the same thing.

Nevertheless, the reality tells a different story, from the statistics it is obvious that white Brazilians have more opportunities accessing education, work, and a higher standard of living. Despite the race-mixing, the white Brazilian population still occupies the top of Brazilian society, while black and brown people are largely struggling in poverty; Racial democracy is a myth and never actually existed. The colour classification, which has been promoted as a wonderful racial democratic system, sugars up the racial differences and inequality by obscuring the concept of race. In fact, colour and race are the same thing.

The custom of face-whitening in Japan goes back to

The custom of face-whitening in Japan goes back to