by Sarah Aartila

From the many mangas about the pure girl, if she were judged according to western philosophy on the case of chastity she would be described as a ‘slut’. The Western philosophy praises individualism, straightforwardness and linear logic, unlike Eastern philosophy which believes in a circular logic with both sides given equal due, and collectivism which sees what is best for the group as a whole. It is true that trafficking is an issue, but what can be done when poor countries have an ever increasing population and a shrinking of available jobs?

Throughout the world women have been and still are considered second class citizens whose only worth is to be a commodity. From the dagongmei in China who toil away to make home better in the factory via honest work, to the foreign hostesses of Japan who freely or sometimes unwillingly offer extra services. These women have freely left home and while many do it for individualistic reasons, most still send money home. Not all hostesses are trafficked nor are all of them illegal aliens (Parreñas 2011). The returning migrant worker comes home a hero. They are pressured like peers by the bar into getting requests. Requests come via promised sex. Some are forced yet they are not the majority like Noini who was forced into prostitution, yet Noini returned again for hostess work. According to Noini:

“We return from Japan with lots of presents and (are) well-dressed. We are the dream of any girl who wants to help her family. I could never tell a Filipino what I told you. They would consider me the lowest possible person in the world. I could not face that. Everyone here pretends” (Schmetzer 1991).

These women sacrifice themselves for the greater good of making the lives of their families at home better. To them being a hostess is better than being a nanny in a middle eastern country where they have a greater potential to be beaten. The salary of £30 an hour offers more buying power than a professional job (Quinn 2012). Besides such pay is fuelled by the many companies who pick up the tab for their salarymen. Many claim that the reason for such clubs is due to Japanese males who fear rejection from Japanese women and that Japanese men look down on all other asians. Also many Japanese people do not like the idea of Filipino women taking care of their elderly. Besides these views justify the right of these men to harass women on the job.

In order to improve the lives of these workers laws Parreñas suggests that laws should be created to protect such women from sexual harassment. These women shouldn’t even be considered as migrant workers, but rather as contract workers or indentured servants as many now can’t enter without the rigorous training required of those entering with an entertainment visa. What was originally intended to eliminate trafficking; the strict regulations for an entertainment visa has caused more to become contract workers. Perhaps the West is meddling too far into the East, trying to press Western morality into an Eastern mindset.

In the end these women are faring way better than their at home counterparts and are helping their country. No one may feel proud about such work as they keep it a secret from home, but even with the Western morality that has been pressed onto the Philippines Eastern morality still seems to prevail overall.

References

Schmetzer, U. (1991, November 20). Filipina Girls Awaken To A Nightmare. Chicago Tribune, 1-2. Retrieved October 28, 2014, from http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1991-11-20/news/9104150088_1_recruiter-japan-filipina/2

Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar. 2011. Illicit Flirtation: Labor, Migration, and Sex Trafficking in Tokyo. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Quinn, S. (2012, September 10). The grim truth about life as a Japanese hostess. The Telegraph. Retrieved October 28, 2014, from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/lifestyle/9524899/The-grim-truth-about-life-as-a-Japanese-hostess.html

by Umene Shikata

by Umene Shikata

The custom of face-whitening in Japan goes back to

The custom of face-whitening in Japan goes back to

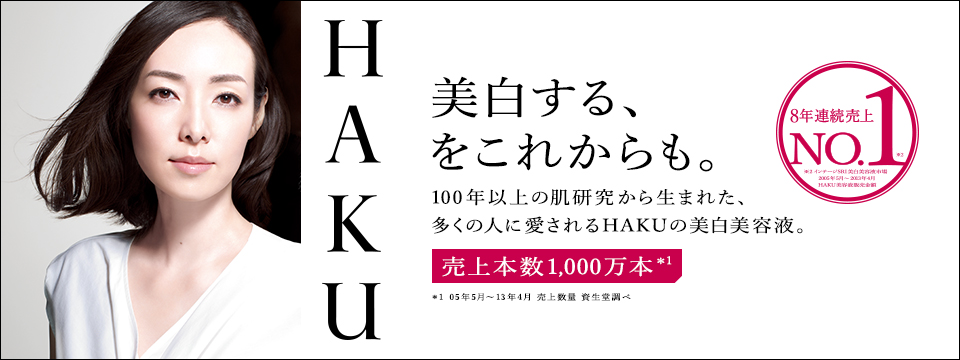

In her research on Japanese whiteness, Mikiko Ashikari (2005) tries to explain where the idea of a specific white skin among the “Japanese race” comes from. According to Ashikari, it seems less likely to be from Caucasians’ influence, since Japanese women considered Caucasian skin as “rough, aged quickly and had too many spots” (Ashikari 2005:82). The idea of white skin in the Japanese society is even more specific than any other features that could define the idea of being “Japanese”. Although Japanese change their hair color with dying products, their eye color with contact lenses, and their physical features with plastic surgery, they would never change their skin color because “the notion of Japanese skin works as one medium to express and represent Japaneseness” (Ashikari 2005:76). As Ashikari notes, by defining a specific skin color to their race, Japanese people are even able to reject the Okinawan people as a “second-class citizens” (Gibney quoted by Ashikari, 2005, p. 80).

In her research on Japanese whiteness, Mikiko Ashikari (2005) tries to explain where the idea of a specific white skin among the “Japanese race” comes from. According to Ashikari, it seems less likely to be from Caucasians’ influence, since Japanese women considered Caucasian skin as “rough, aged quickly and had too many spots” (Ashikari 2005:82). The idea of white skin in the Japanese society is even more specific than any other features that could define the idea of being “Japanese”. Although Japanese change their hair color with dying products, their eye color with contact lenses, and their physical features with plastic surgery, they would never change their skin color because “the notion of Japanese skin works as one medium to express and represent Japaneseness” (Ashikari 2005:76). As Ashikari notes, by defining a specific skin color to their race, Japanese people are even able to reject the Okinawan people as a “second-class citizens” (Gibney quoted by Ashikari, 2005, p. 80). Actually, Japanese whiteness has its roots even before the Black Ships arriving in Japan during the 16th century. It is said that during Nara Period (710–94) and Heian Period (794–1185), Japanese women were already using diverse products to light their skin tone (Kyo 2012). The ideal of white skin is also found in a lot of literature of this period such as the Diary of Lady Murasaki and Tale of Genji (Kyo 2012). Back in the Heian Period, women would blacken their teeth and shave their eyebrows. Nowadays nobody would shave their eyebrows as a sign of beauty but the idea of white skin as the ideal of beauty among Japanese women is still a recurrent topic in Japanese society.

Actually, Japanese whiteness has its roots even before the Black Ships arriving in Japan during the 16th century. It is said that during Nara Period (710–94) and Heian Period (794–1185), Japanese women were already using diverse products to light their skin tone (Kyo 2012). The ideal of white skin is also found in a lot of literature of this period such as the Diary of Lady Murasaki and Tale of Genji (Kyo 2012). Back in the Heian Period, women would blacken their teeth and shave their eyebrows. Nowadays nobody would shave their eyebrows as a sign of beauty but the idea of white skin as the ideal of beauty among Japanese women is still a recurrent topic in Japanese society.