Red Light district in Amsterdam: Dark shadows cast by global flesh trade. (Copyright © 1996-2000 Bruno J. Navarro/Fotophile.com)

Anonymous student post

Human trafficking entails recruiting, transporting and harbouring of a person through “coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power, as well as abuse of vulnerability of women” (Clark 2003). It is a low risk, high reward endeavor for those who organize it. Women in impoverished countries have limited options for supporting themselves and their families, leading them to look for work outside of their country of origin, making them vulnerable to a trafficker’s false promises of high-paying jobs as a waitress or entertainer. Traffickers, exploiting the economic need, often confiscate the victims’ travel documents during or after transport or physically imprison them in brothels, houses, or bind them by dept. In some cases the women choose to subject themselves to the traffickers knowing the danger, as they might end doing the same work at home for lower pay.

People are trafficked into the sex industry not to satisfy the demands of the traffickers, but that of the purchasers. Hence, human trafficking is a lucrative market for all persons involved, except for the women, and/or children involved. Even if it can be argued that some women decide by themselves to subject themselves to traffickers, the majority of women are not aware of what kind of labor that is expected by them when arriving at another country. Moreover, traffickers are extremely good in manipulating the truth and take advantage of the poor living conditions the women have in their country of origin. Therefore, it can be stated that it is a chain of people who take advantage of vulnerable women in mainly impoverished countries to satisfy their demands. Moreover, in some countries it is a extremely profitable market, and therefore government in impoverished countries take rather small action towards the traffickers. One reason is that the sex industry can be linked to tourism. It can be argued that Asian countries have a different view on women than for example, the western culture, and therefore become an popular destination for people who not originates from the Asian culture. It can be difficult for government to stop trafficking and sexual industry when there is a growth in the tourist sector, and especially since it may require a lot of assets to track down and get evidence against traffickers.

Trafficking humans is a cross border movement where several actors are involved. It is not only humans that are smuggled between borders, it is a complex net where cash flow and illegal documents cross borders around the world. Even if there are several International laws against human trafficking it is as mentioned extremely difficult to track down the trafficker. Moreover, it is also difficult to find women, and / or children that are willing to testify against the smugglers, since they are afraid that their families will be either hurt by the traffickers, or feeling ashamed by their daughter’s occupation. It is also very difficult for the vulnerable women to escape their situation since they are being illegal immigrants in the hosting country, and some countries treat illegal immigrants in a rather harsh way, and the fear of police and immigration officers forces the women to maintain in the hands of traffickers, sex buyers and other persons involved in the profit chain.

Reference

Clark, Michele A. 2003. “Human Trafficking Casts Shadow on Globalization.” YaleGlobal, April 23. http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/human-trafficking-casts-shadow-globalization

by Umene Shikata

by Umene Shikata

by John Wang

by John Wang

The custom of face-whitening in Japan goes back to

The custom of face-whitening in Japan goes back to

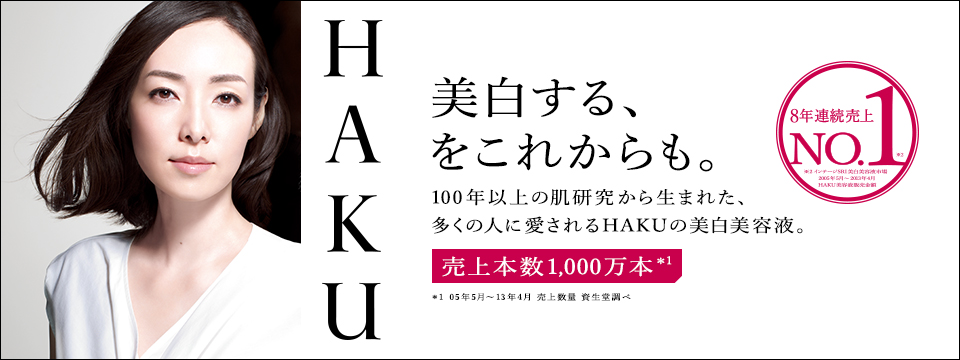

In her research on Japanese whiteness, Mikiko Ashikari (2005) tries to explain where the idea of a specific white skin among the “Japanese race” comes from. According to Ashikari, it seems less likely to be from Caucasians’ influence, since Japanese women considered Caucasian skin as “rough, aged quickly and had too many spots” (Ashikari 2005:82). The idea of white skin in the Japanese society is even more specific than any other features that could define the idea of being “Japanese”. Although Japanese change their hair color with dying products, their eye color with contact lenses, and their physical features with plastic surgery, they would never change their skin color because “the notion of Japanese skin works as one medium to express and represent Japaneseness” (Ashikari 2005:76). As Ashikari notes, by defining a specific skin color to their race, Japanese people are even able to reject the Okinawan people as a “second-class citizens” (Gibney quoted by Ashikari, 2005, p. 80).

In her research on Japanese whiteness, Mikiko Ashikari (2005) tries to explain where the idea of a specific white skin among the “Japanese race” comes from. According to Ashikari, it seems less likely to be from Caucasians’ influence, since Japanese women considered Caucasian skin as “rough, aged quickly and had too many spots” (Ashikari 2005:82). The idea of white skin in the Japanese society is even more specific than any other features that could define the idea of being “Japanese”. Although Japanese change their hair color with dying products, their eye color with contact lenses, and their physical features with plastic surgery, they would never change their skin color because “the notion of Japanese skin works as one medium to express and represent Japaneseness” (Ashikari 2005:76). As Ashikari notes, by defining a specific skin color to their race, Japanese people are even able to reject the Okinawan people as a “second-class citizens” (Gibney quoted by Ashikari, 2005, p. 80). Actually, Japanese whiteness has its roots even before the Black Ships arriving in Japan during the 16th century. It is said that during Nara Period (710–94) and Heian Period (794–1185), Japanese women were already using diverse products to light their skin tone (Kyo 2012). The ideal of white skin is also found in a lot of literature of this period such as the Diary of Lady Murasaki and Tale of Genji (Kyo 2012). Back in the Heian Period, women would blacken their teeth and shave their eyebrows. Nowadays nobody would shave their eyebrows as a sign of beauty but the idea of white skin as the ideal of beauty among Japanese women is still a recurrent topic in Japanese society.

Actually, Japanese whiteness has its roots even before the Black Ships arriving in Japan during the 16th century. It is said that during Nara Period (710–94) and Heian Period (794–1185), Japanese women were already using diverse products to light their skin tone (Kyo 2012). The ideal of white skin is also found in a lot of literature of this period such as the Diary of Lady Murasaki and Tale of Genji (Kyo 2012). Back in the Heian Period, women would blacken their teeth and shave their eyebrows. Nowadays nobody would shave their eyebrows as a sign of beauty but the idea of white skin as the ideal of beauty among Japanese women is still a recurrent topic in Japanese society.