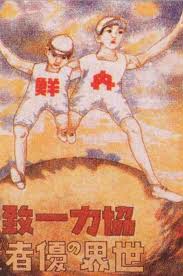

鮮, referring to Korea, and 内, literally meaning inside, representing Japan

Student post

In Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson argues that the emergence of “official nationalism” was, to a large degree, incited by the national movement in the American nations. Old dynastic groups felt the need to merge nation and empire in order to retain power that is competitive to that of establishing imagined communities. Among such empires, Anderson uses Japan as one example.

Japan officially annexed Korea in the year 1910, and the following 9 years were called the Military Police Reign Era. This era was characterized by massive violence, frequently involving deaths of civilians. The Military Police Reign Era was abruptly ended in March 1st of 1919 when, for the first time, the Korean public across the peninsula joined the demonstration to resist against repressive Japanese colonial rule. Realizing the limitation to rule by force, the government-general switched its policy to “cultural policy”, which was an attempt to break down Korean identity and culture (partly) through forbidding usage of Korean language. In schools, students were severely punished if they spoke in their language, and such punishment methods included forcing children to beat each other if one of them talked to the other in Korean. Through education and forced visit to shines (and many other ways), the government-general laid the foundation for full mobilization as the tide of war was gradually turning against Japan.

Kuniaki Koiso, Japanese Governor-General of Korea, implemented a draft of Koreans for wartime labor. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Japanese imperialism continued even after the end of WWII. The period between 1945 and 1948 marked the most intensive education movement by the Koreans in Japan of all time. When the liberation was finally achieved in 1945, the Koreans in Japan immediately set up language schools to prepare for repatriation. However, the GHQ, along with the Japanese government, took oppressive measure to interrupt the Korean identity education enforced by the League of Koreans, a group that undertook the management of schools. In 1947, the occupation force issued the sentence commanding Korean schools to follow the direction of the Japanese administration, which basically denied the education right of Korean children. The second directive was issued in March 1948, which stated that the government will shut down the schools by force if the league does not accept the first order. Receiving the directive, enraged Koreans immediately gathered to organize demonstrations. In April 7th, around 10,000 participants in Kobe gathered in front of the school gate to block the police from entering the school. Police resorted to brutality against parents and teachers who strongly resisted. Following such a large scale demonstration, on April 24th, the government took down the order and the GHQ, for the first time, declared the state of emergency in Kobe, which virtually marked the victory for Koreans. Although there are some other political reasons behind the oppressive measure taken by the oppressors, from the fact that the GHQ and Japanese government tried to exterminate Korean educational institutions, it is possible to make an observation that they were aware of the power of language and its potential to be their threat.